One problem when dealing with developer “secrets” in development is accidentally checking them into source control. These secrets could be connection strings to dev resources, user IDs, product keys, etc.

To help prevent this from accidentally happening, the secrets can be stored outside of the project tree/source control repository. This means that when the code is checked in, there will be no secrets in the repository.

Each developer will have their secrets stored outside of the project code. When the app is run, these secrets can be retrieved at runtime from outside the project structure.

One way to accomplish this in ASP.NET Core projects is to make use of the Microsoft.Extensions.SecretManager.Tools NuGet package to allow use of the command line tool. (also if you are targeting .NET Core 1.x , install the Microsoft.Extensions.Configuration.UserSecrets NuGet package).

Setting Up User Secrets

After creating a new ASP.NET Core project, add a tools reference to the NuGet package to the project, this will add the following item in the project file:

<DotNetCliToolReference Include="Microsoft.Extensions.SecretManager.Tools" Version="2.0.0" />

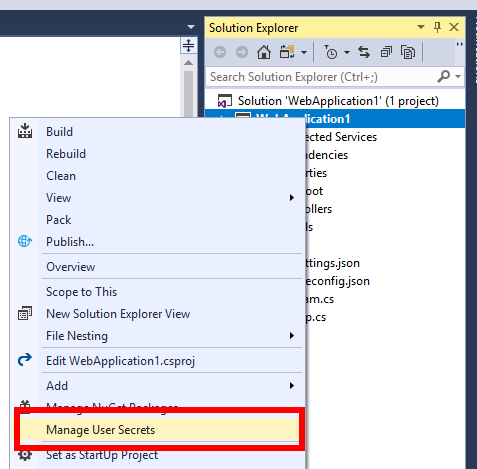

Build the project and then right click the project and you will see a new item called “Manage User Secrets” as the following screenshot shows:

Clicking menu item will open a secrets.json file and also add an element named UserSecretsId to the project file. The content of this element is a GUID, the GUID is arbitrary but should be unique for each and every project.

<UserSecretsId>c83d8f04-8dba-4be4-8635-b5364f54e444</UserSecretsId>

User secrets will be stored in the secrets.json file which will be in %APPDATA%\Microsoft\UserSecrets\<user_secrets_id>\secrets.json on Windows or ~/.microsoft/usersecrets/<user_secrets_id>/secrets.json on Linux and macOS. Notice these paths contain the user_secrets_id that matches the GUID in the project file. In this way each project has a separate set of user secrets.

The secrets.json file contains key value pairs.

Managing User Secrets

User secrets can be added by editing the json file or by using the command line (from the project directory).

To list user secrets type: dotnet user-secrets list At the moment his will return “No secrets configured for this application.”

To set (add) a secret: dotnet user-secrets set "Id" "42"

The secrets.json file now contains the following:

{

"Id": "42"

}

Other dotnet user-secrets commands include:

- clear - Deletes all the application secrets

- list - Lists all the application secrets

- remove - Removes the specified user secret

- set - Sets the user secret to the specified value

Accessing User Secrets in Code

To retrieve users secrets, in the startup class, access the item by key, for example:

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

services.AddMvc();

var secretId = Configuration["Id"]; // returns 42

}

One thing to bear in mind is that secrets are not encrypted in the secrets.json file, as the documentation states: “The Secret Manager tool doesn't encrypt the stored secrets and shouldn't be treated as a trusted store. It's for development purposes only. The keys and values are stored in a JSON configuration file in the user profile directory.” & “You can store and protect Azure test and production secrets with the Azure Key Vault configuration provider.”

There’s a lot more information in the documentation and if you plan to use this tool you should read through it.

If you want to fill in the gaps in your C# knowledge be sure to check out my C# Tips and Traps training course from Pluralsight – get started with a free trial.

SHARE: